Developing Scientific Capabilities to Support Diarrheal Disease Research at the Washington University School of Medicine in Bangladesh, and how I’m grateful to the students of Washington University

What are their vulnerabilities? And can they give voice to that so that we can create questions together for them to pursue, that they have ownership of, that they have joy pursuing, and where they will feel supported, not only in terms of the relationship they have with me, but their relationship with the community of people that surround them.

Fundamentally, it begins with the gift of attention and trying to look at the world through another person’s eyes, understand what inspires them, how they view their needs.

Professor Gordon strongly believes in working in a supportive environment where each person, whether in Dhaka, Bangladesh, or in his lab at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, feel safe enough to take the chance to develop themselves to the best of their abilities.

Because they in St Louis, they are doing the assays, the DNA work, the sophisticated work, but then it would be great for them to look at the conditions in which the patients live slip, and how do the patient’s look like you know. So I believe that that’s going to empower them more.

I think that’s important, not only to the journey of the lab and our relationships with one another, but also our connections to our colleagues in Bangladesh.

Washington University has a program to allow people who are from the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research to come for six months at a time.

But also to empower young individuals, once they acquire this knowledge, to be able to pursue that, so their careers can mature and develop in the locales where they practice their science.

The ability to evolve and deploy technology at a site where the burden of disease is great, the training of very talented individuals and they become familiar with these tests, to create durable programs so that these capacities can be deployed for a variety of different problems.

The grant money that Professor Gordon and his associates received will help strengthen international collaboration by empowering people.

In a supportive and trusting environment, we can share ideas, and at the same time not be afraid to say “I don’t understand.” That’s a shared belief that discovery and innovation occurs, is born, in a very caring and respectful environment, so that we could share ideas

I am so thankful for the remarkable group of students that come to the lab to share their lives with me, each embarking on a unique journey reflecting their hopes, dreams, their previous life experiences, their existing strengths, as well as their ambitions for acquiring new capabilities.

We are thousands of miles away from each other. We meet nearly every week now. And this is on the Zoom platform. We never think that you know, that it has to be very formal. We all are members of the same team, because we have worked so closely together.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-02061-2

What are the contributions of microbes in the gut to the healthy growth of infants and children? A case study of the Hadza people in Bangladesh

They wanted to know: what are the contributions of this magnificent and invisible world of microbes in the gut to the healthy growth of infants and children?

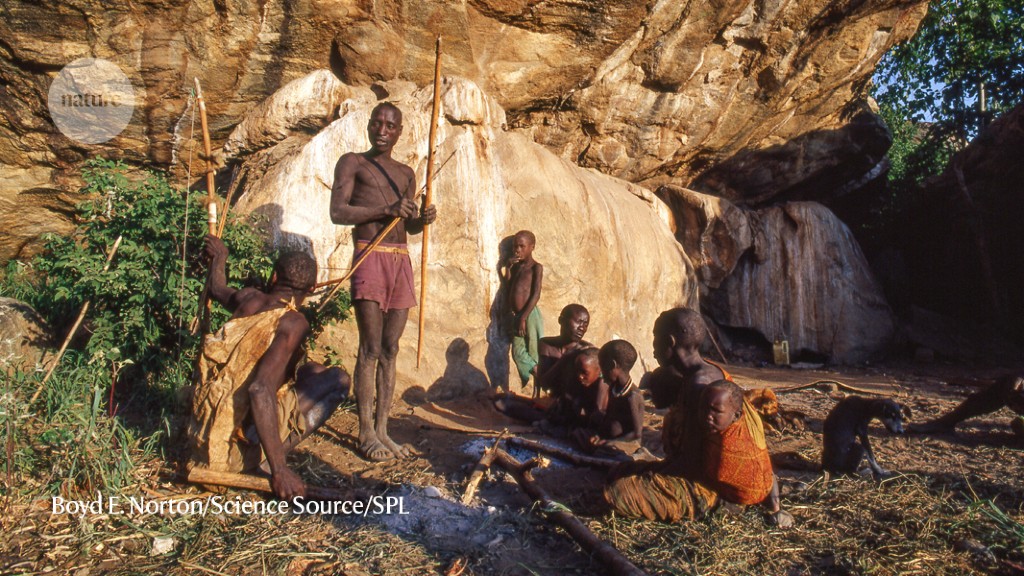

The Hadza people had fecal samples taken from them in the three previous years. For comparison, the team also generated sequences from stool samples collected from four groups of people in Nepal in 2016, and samples from Californian participants in a 2021 study2 that explored how diet affects the microbiome.

There can be issues with children’s nutrition. It can affect adults in low and middle income countries like Bangladesh. Most often, we come across children and women who suffer from this wretched condition.

Dr. Ahmed has been working at the icddr,b for about 36 years, and is now also the executive director there. Dr Ahmad has been studying nutrition since he started his job at icddr.

My name is Tahmeed Ahmed, and I’m Bangladeshi. I am a doctor. At the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh I work as a medical scientist.

It became apparent that relationship sharing was important for a foundation of beneficial relationships in the gut.

The Collaborative Biology of Dr. Jeffrey Gordon, Professor in Washington University School of Medicine, discusses his childhood dreams of becoming an abiotic scientist in the gut

They were able to build complexity. First inputting one member, then another, in an organized and defined way to start understanding the dialogue going on in there,

germ-free animals were taken to environments where there wasn’t any microbes. And initially, one at a time, possible members of the human gut, microbial community, their microbiota,

So their big question is: With an astronomical number of interactions going on in the gut, how can we understand the connections and conversations going on in there?

The gut is teeming with activity. There are lots of microbes living there. And what Dr Gordon and his collaborators are asking is whether the microbes living in the gut are communicating with the cells that line the gut.

Working Scientist is a Nature Careers podcasts. I am Julie Gould. Jeffrey Gordon, a professor in the Washington University School of medicine in St Louis, USA spoke about his childhood dreams.

The Hadza People: the diversity of their microbiomes and how their Western lifestyle affects their development and their urbanization, and how inflammation could be triggered

At a time when the Space Age was beginning, I was among a group of my generation who looked to the sky to imagine what it would be like to see the Earth from other planets. My dream when I was a child was to be anastrologer and travel to Mars to look for new life.

And then I suggested that “Look, the kind of disease, under-nutrition, that I see is just opposite to what you see in the United States and other developed countries.

It was early in the morning and we were taking breakfast. We were talking. I asked him about the work on overweight that he had done, and the work that he had done in Africa.

I think that an environment and formed support for one another that is just the idea that there is ashared spirit underpins the foundations for interdisciplinary research and for human flourishing. There’s a shared hope, trust, there’s a kindness and generosity and a shared sense of purpose that equals the sheer joy.

The human gut is teeming with trillions of microbes, but most studies of this vast community have focused on people living in urban regions. The Hadza people are a group of hunter-gatherers who lived in northern Tegucigalpa, which is where the team compared the Hadza people with people in Nepal and California. The study found that the Hadza have more gut germs than other people, and that the Western lifestyle seems to affect the diversity of gut populations.

Matthew Carter, a co-author of the study, says the findings show that the differences between people who live in non-industrial lifestyles and those who live in industrialized societies are more pronounced.

Furthermore, gut-microbe species commonly found in industrialized populations often contained genes associated with responding to oxidative damage. Matthew Olm, a microbiologist at Palo Alto, says the team suspects that inflammation in the gut could cause those genes to be damaged. “If you have a state of chronic inflammation, it would make sense that your gut microbiome has to adapt,” he says. These genes were not detected in the Hadza microbiomes.