The Road Towards a Safe and Secure mpox Vaccination for Children and Families in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

There are also major logistical challenges to rolling out an mpox vaccination effort, given that most of the cases are in remote areas and parts of the country face violent unrest. Now that the DRC has declared its intent to use two types of mpox vaccines, its National Regulatory Authority is meeting for a vaccine assessment. While mpox vaccines are likely months away, these steps are being heralded as progress – as is the country’s acknowledgement of the scale of the concern.

“Small children [with mpox] can become dehydrated very quickly. When you have enlarged lymph nodes in the neck and sores in the mouth, children can’t eat or drink. Without access to rehydration methods, nasogastric tubes, and IV fluids, the children have a high risk of death and disease, which is why we’re seeing it in the data.

Diagnosing mpox in the DRC: How do we go about addressing the epidemic? Commentary on Nic Naisedembi, director of the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention,

I would tell you: Declare! Because, by declaring, you have access to the drugs, you have access to the vaccines. We shouldn’t have to go through all the approval processes. The door for international support to mobilize resources will be opened by that.

This could lead to rapid spread of the disease with relatively few symptoms, according to Nic Naisedembi, a researcher at the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. “The DRC is surrounded by nine other countries — we’re playing with fire here,” he says.

Ndembi says a lot of considerations must be taken into account before an official declaration can be issued. Many countries vividly – and bitterly – remember how travelers from numerous African countries were banned after Botswana and South Africa shared news about the discovery of Omicron, which was then a new strain of COVID. The bans cost countries money and drew criticism since they didn’t get the same response in Europe. He says it’s very sensitive.

The concern is heightened because the type of mpox circulating, called Clade I, is 10 times deadlier than the type of mpox that caused a worldwide outbreak in 2022. There are at least 311 mpox deaths this year; 10% of Clade I cases are fatal. Evidence shows that a new strain of mpox has been circulating among sex workers in the eastern part of the DRC and seems to be sexually transmitted. Clade I has never been known to transmit sexually.

In addition to the U.S., Europe and Japan, vaccines have been used to fight mpox. So far, they have not been approved for use in most African nations.

Other countries and international organizations have been working to balance their desire for quick action against the DRC’s right to address its own health plans and priorities. There are several health challenges that the nation is juggling.

“We’ve been doing a lot of groundwork and building support and trying to strengthen things. “Now, I hope that we’re at a pivot point,” says Dr. McQuiston, the director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Over the next three weeks, we expect to learn a lot about what’s happening on the ground.”

Vaccines for monkeypox virus in the South Kivu and Burundi: The first large outbreak of human-to-human transmission in Nigeria

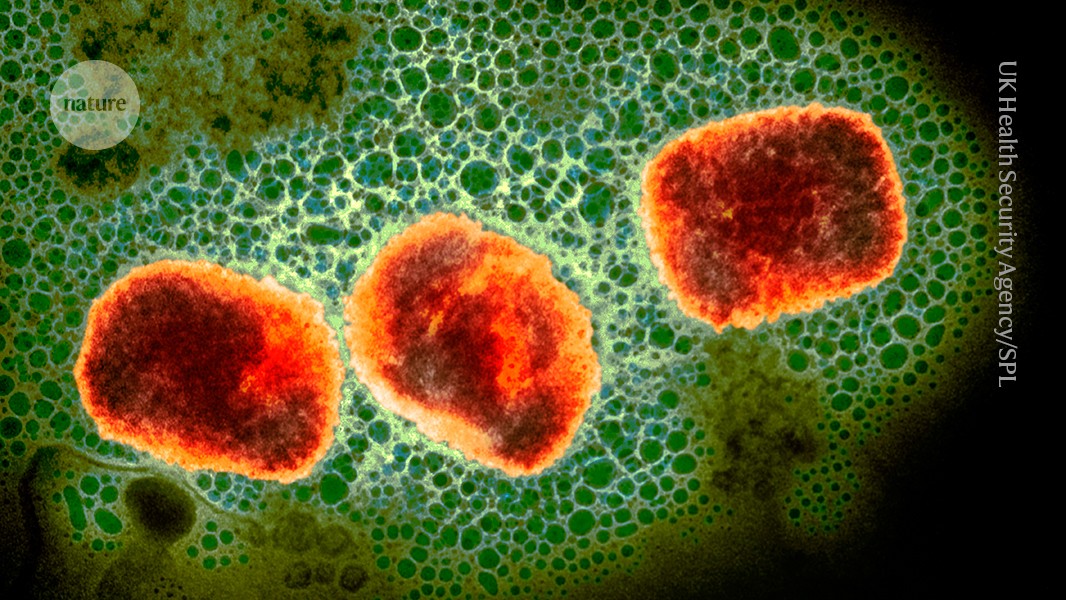

The monkeypox virus can cause painful, fluid-filled lesions on the skin and, in severe cases, death. The monkeypox virus is still called mpox despite the fact it was renamed. The virus persists in wild animals in several African countries, including the DRC, and occasionally spills into people.

The first large reported outbreak with human-to-human transmission occurred in 2017 in Nigeria and was caused by a strain called Clade II, which is less virulent than Clade I. The outbreak caused more than 200 confirmed and 500 suspected cases. At the time, researchers cautioned that the Clade II strain might have adapted to spread through sexual contact.

Making matters more fraught, South Kivu borders Rwanda and Burundi and is grappling with “conflict, displacement, food insecurity and challenges in providing adequate humanitarian assistance”, which “might represent fertile ground for further spread of mpox”, the WHO warned last year.

While the DRC weighs regulatory approval for these vaccines, the United States has committed to providing the DRC with enough doses to inoculate 25,000 people, and Japan has said it will also provide vaccines, says Rosamund Lewis, technical lead for mpox at the WHO. It would take hundreds of thousands of doses to inoculate every individual against the disease, she says.

Data from animal studies are promising, and it is not clear how much protection these vaccines will give against the clade I mpox, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers are also conducting a trial in the DRC of tecovirimat, an antiviral that is thought to be effective against the monkeypox virus. Results are expected in a year’s time.

The WHO and the CDC have helped to procure equipment that will allow for more rapid diagnosis of the disease in the DRC, especially in rural areas, Lewis says. The rapid deployment of African health officials gives her hope that they can control the outbreak before it begins to spread.