Ending the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: The Effects of an Epidemic on the American Household Income: Implications for the Future of the Food Crisis

Because the emergency allotments increased every SNAP recipient’s benefits to the maximum amount, the households with higher incomes, previously receiving the minimum amount of SNAP benefits, will see the largest decrease in their monthly allowance. The households that receive the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, are still low-income despite being higher income than other recipients. Many elderly recipients receive less Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits because of their Social Security income.

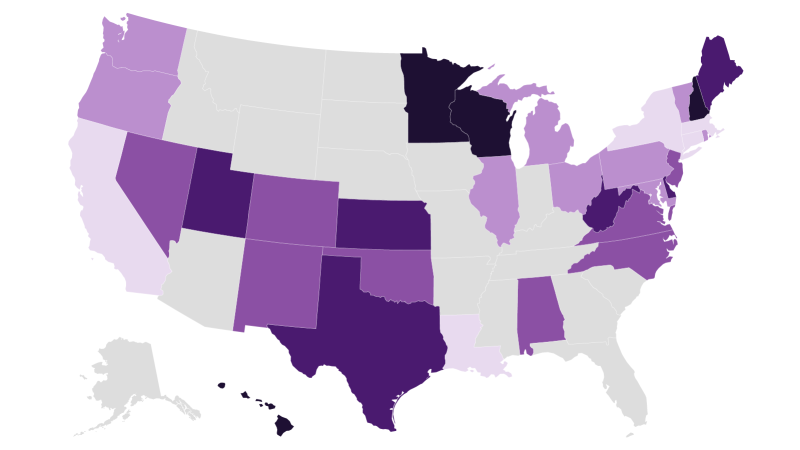

Thirty-three states and D.C. are still giving the boost, and benefits will return to pre-pandemic levels in March. Benefits will return to normal in South Carolina this month. Emergency allotments had already ended everywhere else.

The steepest drops will disproportionately hit elderly people, she said. Older adults who qualify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program will have their benefits decrease in March, from $281 per month to just $23.

States with more households closer to the edge of that benefit “cliff” will see the largest average loss of benefits. At least four states will see household benefit losses of more than $200 a month.

The food stamp recipients will receive less benefits as the hungerrelief program ends three years after Congress approved it.

Food scarcity can affect everyone, even though every participant will be affected. Black households and households with children are more likely to experience food scarcity, according to data from the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

With the end of this “temporary boost,” Rosenbaum says families already feeling the pressures of inflation are going to face more difficulty affording groceries.

While the Great Recession saw increases in food poverty, the food crisis held steady and reached 20-year lows for families with kids, due to Covid relief efforts.

There is no other option except to end this program because of research showing that ending it will increase food insufficiency and keep every recipient at the maximum benefit level indefinitely.

“There’s no way to end it without causing harm because starting it reduced harm,” Whitmore Schanzenbach said. Hopefully, we will be able to absorb the increased hardship from this economy, since it has come out of this epidemic with a strong economy.

“It’s something that people are going to notice,” said Dottie Rosenbaum, director of federal SNAP policy at the center. It is $3 billion a month that is going to food that is not here anymore.

The food banks and pantry are already stretched thin due to increased demand due to the surge in grocery prices, so they are bracing for a new spike in need.

The latest federal data shows that more than 42 million Americans received food stamps in November. Without the pandemic boost, the average food stamp benefit will come to about $6 per person per day in 2023, instead of about $9, according to the center.

Food stamp recipients in states that already terminated the program are feeling the pinch, said Stacy Taylor, head of policy and partnerships at Propel, a software company that provides an app to check SNAP benefit balances.

Those who live in these states report higher rates of skipping meals, eating less, relying on others for meals and visiting food pantries than their peers in states that continued the emergency allotments, she said, citing Propel’s monthly surveys of its more than 5 million users.

For Pam Ford, the $95 monthly boost has meant that she could buy more milk, fresh fruits and vegetables, crackers and peanut butter for her sons, ages 4 and 1. Once she heard it was ending, she started using her main monthly benefit of $645 to stock up on steaks, ground beef and canned fish for future meals.

Food security after the initial pandemic boost: How the Atlanta Community Food Bank can respond to a growing hunger crisis through its end-of-boosted emergency allotments

The Cleveland resident is creating dishes that will stretch out her supplies, such as Mexican dishes that require beans and rice. She is planning to serve more breakfast meals.

The emergency allotments kept 4.2 million people out of poverty in 2021, lowering poverty by nearly 10% and child poverty by 14%, according to an Urban Institute study.

In addition to the cessation of the emergency allotments, some food stamp recipients could face additional hurdles once the public health emergency ends on May 11. Several other provisions, including the suspension of the three-month time limit for certain adults without disabilities and without children who aren’t working, will be ended at that time.

Ford decided to go to the food pantry to prepare for end of boost. Anti-hunger groups are expecting more and more people to do the same.

Feeding America, a nationwide network of 200 food banks and 60,000 pantry and meal programs, says there is a hunger crisis.

“It was just something that happened suddenly and jarringly to families that are already struggling to afford the basic essentials of life, like rent and gasoline and health care and, of course, food,” Hall said.

The Atlanta Community Food Bank saw a 40% spike in demand in December, compared with the same month a year earlier. Between a third and half of that jump was likely due to the state ending the emergency allotments last summer, said Kyle Waide, CEO of the nonprofit, which provides nearly 10 million pounds of food a month to almost 700 community partners, including pantries, senior centers, schools and shelters, in Georgia.

“If you’re someone who cannot meet your basic needs with your existing resources, every $10, $20 or $30 matters. It allows you to get a little bit more nutrition for your family,” Waide said.

Tari Aguilar will have to turn to a food bank in order to get canned food, vegetables and bread because of the end of her emergency allowance. She could treat herself to a fast-food meal once a month because of the increase.

Social Security is her main source of income, and while those payments include a cost-of-living adjustment, it hasn’t kept up with the increase in rent and other expenses, Phares says. The pandemic boost in SNAP allotments helped her eat well and preserve her Social Security money for other things. She will have to do more with less.

“I’m going to figure out how to make it stretch,” Phares says. One strategy to save money is to cut back on meat and fresh produce and stock up on cheaper foods, such as crackers, bread and rice, she says. But Phares knows this isn’t good for her.

“The cheapest stuff is the less healthy stuff,” Phares says. “I learned that, because I gained a lot of weight eating on the cheaper stuff — the starches, the crackers. She says that she’s going to have to figure that out now she’s gotten herself to a better weight.

Scaling up Food Security with SNAP Benefits: Implications for the Mid-Ohio Food Collective, a Food Bank, and the Alabama Food Distribution Network

Over 9 million older people ages 50 and up were considered “food insecure” in 2020 because they sometimes couldn’t afford all the food they needed. According to the group No Kid Hungry, an estimated 9 million children live in food-insecure homes. Overall, about 10% of U.S. households experienced food insecurity at some point in 2021.

“SNAP remains our most powerful tool to fight hunger,” she says. “It’s found to be linked to improved health, education and economic outcomes and to lower medical costs,” she says.

A recent CDC report found 1 in 2 young children in the U.S. don’t eat a daily vegetable, but most consume plenty of sugary drinks. And about 1 in 5 children in the U.S. have obesity.

The Bipartisan Policy Center’s Food and Nutrition Security Task Force recommends strengthening food and nutrition security through the farm bill, including expanding the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program that gives SNAP recipients more money to buy fruits and vegetables.

This is similar to the Double Up Food Bucks program from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which doubles the value of SNAP benefits when used to buy produce at farmers markets and other venues. Another idea is to strengthen standards for retailers to encourage a wider variety of nutritious foods in stores.

At the end of September, the farm bill is set to expire, which is usually reauthorized every five years. It’s a huge piece of legislation that regulates everything from agriculture subsidies to nutrition programs.

Mitchell says there’s lots of momentum — from a wide variety of groups, policymakers to health care organizations — to scale up programs that can be beneficial. Mitchell points to the use of benefits at farmers markets as well as the creation of a food pharmacy where you can use your benefits to purchase healthy food to improve your health outcomes

There are many people in need at the moment. The Mid-Ohio Food Collective, Ohio’s largest food bank, has seen an increase in the need for its services even before the emergency benefits ran out.

FRAC is calling for increased benefits as a “hunger cliff.” Recipients in 32 states and the District of Columbia are affected this month.

Linda Jones is a co-founder of a food distribution nonprofit based in Alabama, one of the states that will suffer due to the end of the extra benefits.

“They’re just already down and out. They don’t have very much to begin with,” she said in an interview with NPR. It’s extra hard on them if you take something else from them and the prices go up.

“If people are hungry, and the federal government is going to do less about it, that doesn’t mean things will get better,” Vollinger said.

The New York Extension of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is Not for Low-income Families, but for Non-farming Families

Instead, the costs are shifted, she explained — to states, to local governments, to charities, and within the households themselves, as recipients work to recalculate how to spend their limited income.

New Jersey was the first state to pass legislation regarding the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or nutrition assistance programs, in June of last year. If the federal government determines you do not qualify for a lower amount of benefits, a state-funded supplement can be used to make up the difference.

SNAP eligibility is like federal income tax in that applicants can deduct eligible expenses from their total income in order to figure out how much in SNAP benefits they’re eligible for.

Among the deductible expenses are certain medical costs, or the costs of child care or disabled adult care if you are working, looking for work or in school or training. You may be able to deduct legal child support payments.

The costs of many services have gone up in the past two years as inflation has driven up prices, so it’s a good time to reexamine those costs.

“It is not going to make up for the entire cliff, but it can make a difference in the size of the cut that households are experiencing,” Vollinger said.

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children is open to all children up to the age of 5. See if you qualify here.

The Seniors Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program, which gives coupons for fresh produce at farmers markets, may be available to low income people at least 60 years old.

During the Psyvche, many schools provided free meals to all students, but it came to an end last fall. If you call your child’s school you’ll get more information about how to qualify for free lunch and breakfast.

Some nonprofits offer help. Look for programs like Double Up Food Bucks, which doubles the value of EBT payments when purchasing fresh fruits and vegetables at 1,300-some grocers and farmers markets across 30 states.

We will see a big increase. We’re expecting to serve 15% more people,” said Brooke Neubauer, founder of The Just One Project, a Nevada-based food bank, in an interview with NPR. We are welcoming them with open arms.

Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks and food pantries, has an online tool that can help you find a local food bank. The USDA operates ahunger hotline which connects callers with emergency food providers in their community, government assistance programs, and various social services.