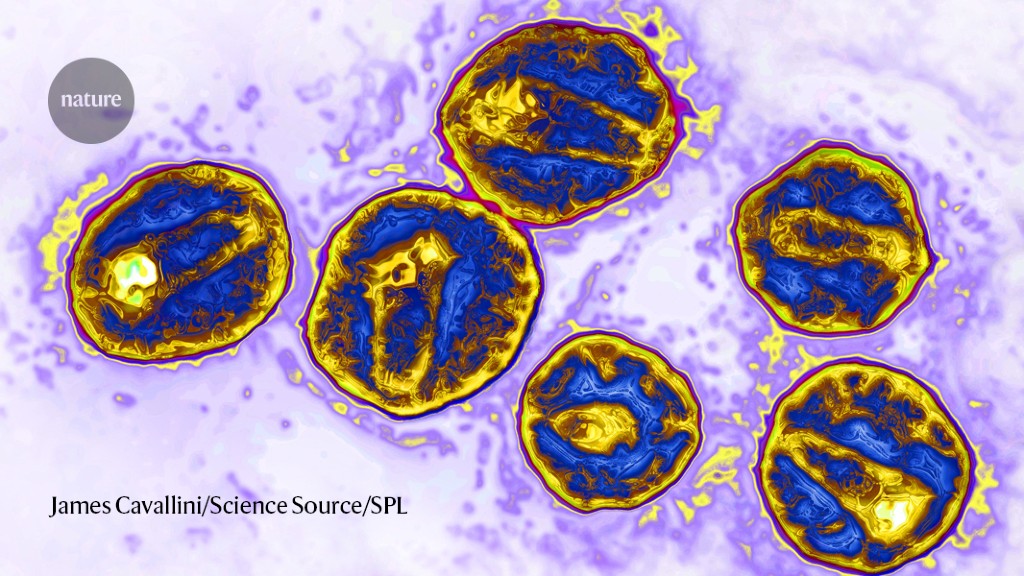

Identifying a viral region in a bone marrow transplant experiment for the treatment of AIDS-positive Timothy Ray Brown with Crispr

An HIV-positive man was the first volunteer in a trial that was supposed to use Crispr to destroy the AIDS-causing virus. He was hooked up to an IV bag to carry the experimental treatment directly into his bloodstream. The man has a virus and the team is trying to clear it through the use of the Gene-editing tools.

The volunteer will stop taking the drugs later this month so he can keep his virus at a safe level. Then, investigators will wait 12 weeks to see if the virus rebounds. They will consider the experiment a success if it wasn’t successful. “What we’re trying to do is return the cell to a near-normal state,” says Daniel Dornbusch, CEO of Excision BioTherapeutics, the San Francisco-based biotech company that’s running the trial.

Gupta agrees, although he adds that in some cases the virus mutates inside a person and finds other ways to enter their cells. It is not clear if theChemo that the people received for their cancer before their bone marrow transplant might have helped to eliminate HIV by preventing cells from dividing was a good idea.

That was an important step toward testing the treatment in people, says Kamel Khalili, a professor of microbiology at Temple University who led the work and is a cofounder of Excision Biotherapeutics. He says that, although they don’t want to eradicate the viral genomes, they do want to cause any disruption in the other part of the human genome. We have to make sure that the HIV region we identified was not related to the human genome.

The stem-cell technique involved was first used to treat Timothy Ray Brown, often referred to as the Berlin patient. In 2007, in order to treat leukaemia, he received a bone marrow transplant in which the cells were destroyed and replaced with stem cells from a healthy donor. The team treating Brown selected a donor with a genetic mutation called CCR5Δ32/Δ32, which prevents the CCR5 cell-surface protein from being expressed on the cell surface. The immune cells are resistant to the virus because they use thatProtein to enter them. After the procedure, Brown was able to stop taking ART and remained HIV-free until his death in 2020.

A true cure would eliminate this reservoir, and this is what seems to have happened for the latest patient, whose name has not been released. The man, who is being referred to as the ‘Düsseldorf patient’, stopped taking ART in 2018 and has remained HIV-free since.

Adam Castillejo, the London patient, seemed to have been cured by the same procedure. Scientists thought that a patient in New York who had been HIV-free for 14 months might be able to be cured.

The team that treated Castillejo believes that the most tractable target for achieving a cure right now is CCR5 and it was reinforced in the latest study.

The patient who received the transplant said in a statement that it had been a very rocky road, and that he wanted to give some of his life to charity.

Timothy Henrich is a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. That several patients have been successfully treated with a combination of ART and HIV-resistant donor cells makes the chances of achieving an HIV cure in these individuals very high.

But it’s unlikely that bone-marrow replacement will be rolled out to people who don’t have leukaemia because of the high risk associated with the procedure, particularly the chance that an individual will reject a donor’s marrow. Several teams are testing the potential to use stem cells taken from a person’s own body and then genetically modified to have the CCR5Δ32/Δ32 mutation2,3, which would eliminate the need for donor cells.